The first Carnegie library in the old county of Midlothian opened at West Calder in November 1904. With a ceremonial golden key, the former British Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery, unlocked the door to a world of free books. The many invited guests – members of the parish and county councils, school board members, library contractors and representatives of the local community eagerly entered, itching to see and marvel at their finished library. After hearing a Dedicatory Prayer by a local minister, the guests looked on as Lord Rosebery presented a number to the librarian for a book – thereafter declaring the library open. Refreshments of tea, cake and wine in the new library rooms followed and that evening, the whole community celebrated at a Ball in the Polytechnic Hall.

The library, a Category B listed building, described as “a jewel of a Carnegie Library” in the Illustrated Architectural Guide to West Lothian, stands in neat, landscaped grounds on a hilly site wedged tight between the A71 and the town’s Harburn Road. West Calder, current population approx. 3,200, and now in West Lothian since a boundary change in 1975, lies four miles west of Livingston and a mile from the distinctive Toblerone-like bulk of the Five Sisters Bing, legacy of the area’s shale-mining industry.

The passing of the Public Libraries (Scotland) Act of 1853 gave burgh councils the chance to have free public libraries – to finance them, councils were granted powers to raise their local rates by 1d in the £. Up to this point, the earliest libraries in old Midlothian were private subscription libraries where book borrowers paid a regular fee to get access to the books. A subscription library had been running in West Calder for many decades but by the 1900s, even with stacks (2,000) of books, only a tiny handful of subscribers used it. The Act was a golden opportunity, decided West Calder’s parish council.

Exactly two years before the new, free library’s eventual grand opening, at a public meeting held in West Calder’s People’s Hall, the parish council’s ambitious proposals for a new, public library were passed by 178 votes to 146. The close vote shows the proposed added burden in higher rates to pay for the project wasn’t a popular or affordable decision. Meanwhile, the parish council knew that, despite winning the vote, it still faced a major financial stumbling block because of the area’s small, rural population – raising local taxes alone wouldn’t be enough to build, equip, maintain a library and employ a librarian. More funding was desperately needed.

Then, like Cinderella, its wish came true. A written request to Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie – the Scot who made his fortune in the steel industry in America – proved a trump card and he donated £2, 500 to the parish council for the construction of a new building. (The Carnegie Foundation helped fund almost 3,000 libraries worldwide).

The dream of a free, public library now tantalisingly within its grasp, the parish council speedily formed a Library Planning Committee, chose a site, and in the New Year, launched a competition for the design of the new library and librarian’s house. The winning design, from six submissions, was the brain-child of Glasgow-based architect, 28-year-old William Baillie. A two-storey design, Baillie’s plans showed the library perched on top with the librarian’s house beneath built into the hill creating a now-you-see it, now-you-don’t effect. A wrought-iron, black spiral staircase inside the library linked both levels. Andrew Carnegie’s crucial contribution in place, the local community rallied to the cause raising £300 for their new library at a fundraising bazaar.

Several months later, the gala occasion of the laying of the library’s memorial stone took place with Mr John Fyfe, managing director of Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company, the biggest employer in the area, invited to do the honours. Speeches done and dusted, a bottle filled with coins of the realm was placed in the cavity of the memorial stone. “Another landmark,” the local paper reported, “And that a very important one in the history of our Village and Parish.”

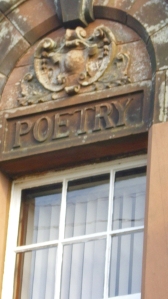

Baillie’s symmetrical building is full of character and period details. The exterior’s red and sand-coloured ashlar (cut and dressed blocks of stone) has the words ‘poetry’, ‘science’ and ‘history’, carved in fat letters above the windows, and Art Nouveau smooth, curved detailing frames the doorway between pedimented Venetian windows. Local firms and tradesmen did the work – masonry work by Wilson and Wallace of West Calder, cost £798 13s 7p. Inside the entrance are original cream, green and yellow glazed tiles. Half-a-dozen steps lead to a wood-panelled vestibule with etched glass panels, a time-capsule crammed with the library’s history. On its walls hangs a framed, faded photograph of the laying of the memorial stone, the memorial stone itself, a bronze plaque “to commemorate the usefulness of the old subscription library” and, off to one side, the 1904 Ladies Reading Room, just feet from today’s library’s modern technology.

The newly-built library received many generous donations of books from local people and businesses. It also welcomed with open arms piles of books (1600 volumes) from the original subscription library. On top of this, an annual budget of £320 had been agreed for the purchase of new books. An approved list was sent to suppliers, inviting quotations from James Thin and Douglas and Foulis in Edinburgh, Maclehose in Glasgow and Mudie’s in London but in the end, small, local firm, James Brown of West Calder, landed the contract.

By the end of its first year, the fast-growing library membership stood at over 800, with 15,500 issues recorded. Book-hungry borrowers were not put off then by the first librarian in post – a stickler for rules – and nicknamed “Auld Wheesht”.

Information from:

A History of West Calder Library by West Lothian District Council Dept. Of Libraries

West Lothian – An Illustrated Architectural Guide by Richard Jaques and Charles McKean

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2013

First published in Lothian Life, April 2013.

Star of paintings, countless photographs, West Lothian Council’s logo and a striking feature in the landscape for 170 years, Almond Valley Viaduct strides purposefully and majestically across the river valley and flood plain.

Star of paintings, countless photographs, West Lothian Council’s logo and a striking feature in the landscape for 170 years, Almond Valley Viaduct strides purposefully and majestically across the river valley and flood plain.

The viaduct took 3 years to build (1839 – 1842) and formed part of the new Edinburgh to Glasgow railway line. The viaduct and railway line are still in use today, Scotrail’s Sprinter trains flashing across it in seconds.

A Railway Guide of 1842, like an early VisitScotland ad, describes the bold curve of the Almond Valley Viaduct, its elegant form and stupendous series of arches, calling it one of the most astonishing achievements of modern skill and enterprise. And how a panorama across the Almond Valley, as enchanting as it is extensive, charms the eye.

Category A listed and 1.5 miles in length, it’s the longest structure on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway. The viaduct is in 2 sections separated by a high embankment 400 metres long. It’s eastern section is made up of 36 ashlar-faced (prepared stonework, dressed or cut) segmental masonry arches, each with a 15.2m span, and up to 21.3m high. The western section has 7 arches, the central and largest arch – with a span of 20.1m – bridges the A89. Strengthening work was carried out in the 1950s and 1988.

Rail travel in the early to mid-19th century was in its infancy with each new line being promoted by a private company. In 1837, the newly-formed Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway Company put together plans to connect Edinburgh and Glasgow by rail. Led by Chairman John Leadbetter, linen merchant and member of Glasgow Town Council, the new company appointed John Miller as engineer.

Miller’s route and design kept the railway as level as possible over as much of the route as he could. Early steam locomotives struggled with gradients, and viaducts and tunnels helped avoid this. The planned maximum gradient was 1 in 880 making the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway the most level main line in the UK.

An Act of Parliament on 4th July 1838 authorised the line giving the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway Company the green light. The adopted route began at a new eastern terminus in Edinburgh – Haymarket – (Edinburgh General Station, later renamed Waverley, didn’t open till 1846), continued over the Almond Valley Viaduct, through the Winchburgh Tunnel, via Linlithgow to Falkirk, and on to its new western terminus at Glasgow’s Queen Street.

The 45-mile route was divided up like slices of cake. Advertisements appeared in the public newspapers for contractors to give in tenders for execution of different sections of the work. The advertisement for the largest slice, including the heaviest engineering work on the line – the Almond Valley Contract – said, “Contract No 1: Being that part of the line extending from near Norton Farm House in the Parish of Ratho to near West Inch in the Parish of Abercorn, and in length 9000 yards or thereby. This contract will include a great extent of cutting and embankment, two viaducts the one across the Almond Water Valley 682 yards long and about 70 feet high and the other across the Edinburgh and Glasgow road 108 yards long and about the same height, a tunnel thro’ Winchburgh Ridge 350 yards long, laying the rails and otherwise completing the lot”.

The 45-mile route was divided up like slices of cake. Advertisements appeared in the public newspapers for contractors to give in tenders for execution of different sections of the work. The advertisement for the largest slice, including the heaviest engineering work on the line – the Almond Valley Contract – said, “Contract No 1: Being that part of the line extending from near Norton Farm House in the Parish of Ratho to near West Inch in the Parish of Abercorn, and in length 9000 yards or thereby. This contract will include a great extent of cutting and embankment, two viaducts the one across the Almond Water Valley 682 yards long and about 70 feet high and the other across the Edinburgh and Glasgow road 108 yards long and about the same height, a tunnel thro’ Winchburgh Ridge 350 yards long, laying the rails and otherwise completing the lot”.

Each contract stated “Contractors shall be completely finished on or before the 1st day of July 1841 with a penalty of £20 per day for every day it shall remain unfinished after that date”.

Leading bridge builder, John Gibb & Son of Aberdeen, won the Almond Valley Contract with a quote of £147, 669 and set to work on their Herculean task in February 1839. (The company made a loss of £40, 000).

Over the next 3 years, the entire route echoed to the sounds of an army of workmen, teams of horses, thunderous explosions and constant clanging of picks and shovels. In the nick of time before the Railway Company’s deadline, and the River Avon Viaduct’s last arch completed, the contractor treated his 160 workmen to a splendid dinner in Linlithgow Town Hall. Down the line, the Polmont section of track finished too, and great celebrations ended with “a merry dance on the green to the strains of bagpipes”.

But the Railway Directors high hopes of a July 1841 completion hit the buffers as other sections of line went unfinished. Penalty clause now kicking in, the Railway Directors complained to the Almond Valley Viaduct contractor that works were falling behind schedule.

In reply, a letter from John Gibb & Son’s Broxburn office said, “At present we have 350 workmen and 25 horses employed on the different cuttings and tunnel on the line – 80 masons, 100 labourers, 18 joiners, 8 blacksmiths and 20 horses employed on the viaducts and bridges besides nearly 150 men with a corresponding number of horses employed in quarrying stone for the viaducts and bridges. This force you will see is not small and will be rapidly increased in the course of a very short time”.

The Directors, whilst reassuring shareholders, urged the contractor to work at night, by “torchlight”. The contractor’s claim for more money for overcoming unforeseen obstructions, unfavourable weather and doing night work cut no ice. On the workmen toiled through a freezing December, and the New Year’s Day edition of the Scotsman, 1842, reports the viaduct’s arches finished, though the banks still incomplete, with hundreds of workmen working furiously.

With huge sighs of relief all round, and the last sweat-lashed shovel flung aside, 18th February 1842 marked the opening ceremony of the Edinburgh to Glasgow Railway. At 1pm a steam locomotive pulling 52 carriages loaded with invited guests arrived at Haymarket from Glasgow, then this train, and another 52-carriage steam locomotive, laden with the Edinburgh contingent – more excited shareholders and invited guests – 1100 people in all – set off triumphantly for Queen Street and a grand banquet. Schools had a holiday and along the line, people waved and cheered this big, loud, newfangled kid on the block. Full steam ahead? Not a bad way to start a New Year.

Information from the Scotsman Archives and the National Library of Scotland.

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, December 2012. Also published in Lothian Life, January 2013.

Inside the Caw Burn storm drain in Pumpherston, it’s pitch black and dangerous. Two figures walk upright clutching high-powered torches as they make their way carefully along the concrete tunnel. Senses on full alert, they feel excited – more aware of things. The smooth, damp walls glisten in the torchlight and the foot-deep water roars and echoes in the confined space – yet they can still hear the traffic above their heads. On the pair trudge for a good 2 hours, deep beneath Houston Industrial Estate, till eventually the space narrows, and they turn back.

Inside the Caw Burn storm drain in Pumpherston, it’s pitch black and dangerous. Two figures walk upright clutching high-powered torches as they make their way carefully along the concrete tunnel. Senses on full alert, they feel excited – more aware of things. The smooth, damp walls glisten in the torchlight and the foot-deep water roars and echoes in the confined space – yet they can still hear the traffic above their heads. On the pair trudge for a good 2 hours, deep beneath Houston Industrial Estate, till eventually the space narrows, and they turn back.

Finding out more about Caw Burn storm drain and the risky hobby of urban exploring, I’m in the Pumpherston home of Caroline Robertson and Tina Doyle, a mother and daughter team of urban explorers. Tina explains the Caw Burn drain was built to filter the waste from Houston Industrial Estate and points out the added risk of exploring drains – how heavy rainfall locally and in surrounding areas very quickly raises the water levels. The burn itself once flowed above ground, Caroline says, winding its way across the land where the offices, factories and warehouses now stand. “My dad told me he used to swim in the Caw Burn when he was wee.”

Urban explorers find any kind of derelict, abandoned buildings and hidden structures fascinating. Above ground or below ground it doesn’t matter. Disused factories, old houses, asylums, hospitals, storm drains, culverts, tunnels and bunkers – places the rest of us wouldn’t give a second glance, maybe don’t even know exist, are right up their street. Inside these sites, they photograph or film the uninhabited space. The unspoken rule among urban explorers is, “Take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints.”

Caroline, a Care Assistant in Broxburn, and daughter Tina, dog-lover and rock music fan who works at Linwater Breeding Kennels, remember how their urban exploring began. In 2004 when Tina was 18 years old, they went for a walk in the grounds of the unoccupied Bangour Village Hospital. Spotting a villa’s door hanging open, they popped their heads round it – but were “Too scared to do anything else!” on that occasion. Caroline had worked there and was curious to see what it looked like now. The air of general decay shocked her. Personal things like ornaments lay around in the dust and debris and thinking of all the human stories made her feel sad she says, but, “The history of it all was so interesting.”

Caroline, a Care Assistant in Broxburn, and daughter Tina, dog-lover and rock music fan who works at Linwater Breeding Kennels, remember how their urban exploring began. In 2004 when Tina was 18 years old, they went for a walk in the grounds of the unoccupied Bangour Village Hospital. Spotting a villa’s door hanging open, they popped their heads round it – but were “Too scared to do anything else!” on that occasion. Caroline had worked there and was curious to see what it looked like now. The air of general decay shocked her. Personal things like ornaments lay around in the dust and debris and thinking of all the human stories made her feel sad she says, but, “The history of it all was so interesting.”

Back home and online, Tina discovered a world-wide community of urban explorers, and she and her mum were hooked. Since then they’ve explored more than 100 sites, mainly in the central belt, and many local sites too, like the ROC (Royal Observer Corps) Post in West Calder – a hidden bunker which was a nuclear monitoring post – a shale mine in Mid Calder and East Calder’s Lime Kilns. Tina films each one and loves the creative process of filming, editing and selecting atmospheric tracks before uploading them via YouTube.

Why urban exploring? “It’s like going back in time,” says Caroline. Old houses, abandoned hospitals and anything underground are her favourite places. Her daughter says, “I like the architecture, even seeing things like old wallpaper – it must be like visiting the Titanic, that sense of the past.” She prefers exploring derelict mortuaries but likes underground places too – storm drains (especially Victorian-era drains made of lovely red brick), caves and tunnels – these fascinate her, “You don’t think what’s under your feet.”

Why urban exploring? “It’s like going back in time,” says Caroline. Old houses, abandoned hospitals and anything underground are her favourite places. Her daughter says, “I like the architecture, even seeing things like old wallpaper – it must be like visiting the Titanic, that sense of the past.” She prefers exploring derelict mortuaries but likes underground places too – storm drains (especially Victorian-era drains made of lovely red brick), caves and tunnels – these fascinate her, “You don’t think what’s under your feet.”

Caroline and Tina stress the safety precautions they take and accept that sometimes they’re in places they shouldn’t be. Rotten floorboards, broken glass, somebody sleeping rough are just some of the hazards. “You have to concentrate at all times,” says Caroline, “we know it’s a dangerous hobby, we do this at our own risk.” They don’t scrimp on their gear and have a list as long as your arm – torches, extra batteries, mobile phone, steel-toed boots, sturdy walking boots, gloves, masks in case of asbestos – to mention a few. And, they both say firmly, “If there’s no way in, we don’t touch it, we go away.”

Another local place they’ve explored is the EDS Facility, an industrial site in Livingston’s Kirkton Campus. Built in 1975, it printed Government giro cheques. The plant shut in 2005 making several hundred workers redundant. The local press at the time reported “a near riot” in the building over the terms and conditions of the redundancies.

Caroline remembers the factory at its peak. She lived in Ladywell at the time, and the local residents often talked about the constant thump, thump of the factory’s machines. Now there’s only a stillness and silence in the huge, debris-strewn complex of 6 main halls, plant rooms, and maze of corridors and stairs, the dust-covered phones waiting patiently for a call that’s never going to come. “It was very strange when we were inside filming,” says Caroline, “I kept thinking of all the workers who had lost their jobs.”

Often, empty buildings get demolished, this was the fate of the disused McEwans Fountain Brewery – with its trademark Laughing Cavalier logo – in Edinburgh. But not before Caroline and Tina explored and filmed it, and by doing this, feel they’ve kept the building and its past alive. People are interested in seeing the films and photos on her website Tina says, because they may have worked or lived in these buildings – it brings back memories.

And when West Lothian’s Local History Library made a public appeal for help in identifying the ward in an old photo of Bangour Village Hospital, Caroline and Tina came to the rescue, “ We realised it was ward 21 because of the two pillars and type of doors.” It was another piece in the puzzle for the library.

Both plan more exploring – further afield now Tina’s passed her driving test – no need to pester her brother for a lift any more, “He charged us for the petrol!” says Tina, “he doesn’t like urban exploring.”

To see photos and film footage visit http://www.youtube.com/user/TeEnZiE

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, May 2012

Filed under: West Lothian | Tags: coaching inns, stagecoaches, turnpike roads, West Lothian

West Lothian’s varied travel history includes a 90 year period when stagecoaches ruled the roads. Between 1760 and 1850, stagecoaches thundered to and fro along the three main roads cutting through the county and connecting Edinburgh and Glasgow. Coaching inns, a few of which remain today, like the Torphichen Arms in Midcalder and Livingston Village’s Livingston Inn were purpose-built staging posts strung out along these routes like vital links in a chain, providing food and shelter for passengers and stabling for the hard-working horses. A team of 4 horses could pull a coach at 10 miles an hour for an hour at a stretch, and inns were built at roughly that distance apart.

West Lothian’s varied travel history includes a 90 year period when stagecoaches ruled the roads. Between 1760 and 1850, stagecoaches thundered to and fro along the three main roads cutting through the county and connecting Edinburgh and Glasgow. Coaching inns, a few of which remain today, like the Torphichen Arms in Midcalder and Livingston Village’s Livingston Inn were purpose-built staging posts strung out along these routes like vital links in a chain, providing food and shelter for passengers and stabling for the hard-working horses. A team of 4 horses could pull a coach at 10 miles an hour for an hour at a stretch, and inns were built at roughly that distance apart.

Stagecoaches had names like The Edinburgh to Glasgow Flyer, Rocket, Quicksilver, The Telegraph and The Express and competition to provide the fastest service for the 52 miles between Edinburgh and Glasgow was fierce. Passengers were squeezed in, 10 to 14 per coach, like sardines in a tin. A single fare cost 4 shillings for an inside seat and 2 shillings for outside, at the full mercy of the weather. The journey time was constantly being reduced, taking 9 – 10 hours at the beginning of the 19th century to a record-breaking 3 hours 44 minutes in 1831 in a race between rival companies.

But the key to the success of the stagecoach era were road improvements. Up until the mid 1700’s, roads were little better than beaten tracks, earth trampled flat by countless feet as people went about their day-to-day business – turning into impassable rivers of oozing mud in winter and wet weather. An early attempt to run a stagecoach service in 1678, advertised it would “Leave Edinbro ilk Monday morning, and return again, God willing, ilk Saturday night”.

Roads had to improve and the turnpike system was adopted. From 1752 laws were passed giving powers to Turnpike Trusts made up of local landowners to “make, amend, widen and keep in repair the roads” and tolls were charged for their upkeep. Each Trust took on the responsibility for a stretch of road (anything up to 20 miles). The laws gave the trusts powers to borrow money to build the new road – the security for the loan was the tolls that would be levied on the road-users. The trustees built a toll-house for the toll collector (tacksman) and tollgates as barriers across the road. These improved roads were known as turnpike roads – when a road-user paid the toll, a pike on the tollgate was turned, the gate pushed open and the traveller, pocket a little lighter, carried on his way.

The three Edinburgh to Glasgow turnpike roads of the 18th century were the route through Midcalder/Livingston/Shotts, a route via Linlithgow/Falkirk/Kirkintilloch and a road via Newbridge/Uphall/Bathgate.

Midcalder’s Torphichen Arms dates from 1763 when the turnpike road arrived in the village (today’s A71 mainly follows the route of this old turnpike road). Known as The Lemon Tree Inn when newly built, it was the first stopping point after leaving Edinburgh on journeys between Edinburgh and Glasgow, Edinburgh and Ayr, and Edinburgh and Hamilton. Standing at the edge of the village and sheltered by Calder Wood, the two-storey inn must have been a welcome sight for passengers, coachmen and horses alike, after a bone-shaking 12 mile journey from Edinburgh as the mud-spattered coach clattered across the stone-built bridge over the Linhouse Water and pulled up at the inn’s door. Stable lads watered the horses or changed them for a fresh team. The inn’s stables once stood where the car park is, with more stables through the pend (arch) across the street.

Midcalder’s Torphichen Arms dates from 1763 when the turnpike road arrived in the village (today’s A71 mainly follows the route of this old turnpike road). Known as The Lemon Tree Inn when newly built, it was the first stopping point after leaving Edinburgh on journeys between Edinburgh and Glasgow, Edinburgh and Ayr, and Edinburgh and Hamilton. Standing at the edge of the village and sheltered by Calder Wood, the two-storey inn must have been a welcome sight for passengers, coachmen and horses alike, after a bone-shaking 12 mile journey from Edinburgh as the mud-spattered coach clattered across the stone-built bridge over the Linhouse Water and pulled up at the inn’s door. Stable lads watered the horses or changed them for a fresh team. The inn’s stables once stood where the car park is, with more stables through the pend (arch) across the street.

Built in 1760, Livingston Inn is a white-harled, single-storey solid building with its very doorstep on the old turnpike road. It is said a distinguished visitor by the name of Robert Burns – born the year before the inn was built – once slept under its roof. An arched stableblock adjoins the inn and is the lounge bar today. The inn’s surroundings of traditional cottages and centuries-old church make the scene look much the same as it must have done in the 18th century and it’s easy to imagine the clamour and commotion as a passenger-laden stagecoach arrived.

Built in 1760, Livingston Inn is a white-harled, single-storey solid building with its very doorstep on the old turnpike road. It is said a distinguished visitor by the name of Robert Burns – born the year before the inn was built – once slept under its roof. An arched stableblock adjoins the inn and is the lounge bar today. The inn’s surroundings of traditional cottages and centuries-old church make the scene look much the same as it must have done in the 18th century and it’s easy to imagine the clamour and commotion as a passenger-laden stagecoach arrived.

Fascinating glimpses of West Lothian’s stagecoach past are all around. The story goes that Blawhorn Moss (a National Nature Reserve) near Blackridge gets its name because it was a look-out point for the Glasgow to Edinburgh stagecoaches on the road below. When the watcher saw or heard the coach and horses galloping into sight from the west, he gave a loud blast on a horn, a signal for the local coaching inn – the Craig Inn – to prepare for thirsty travellers and flagging horses.

And tragic accidents happened – a gravestone in Kirkton Kirkyard, Bathgate reads “Here lieth the Mortal Part Of Benjamin Shaw the affectionate, dutiful and only son of Benjamin and Sarah Shaw of St Paul’s Church Yard, London, Who was suddenly kill’d by the breaking down of the Telegraph coach near West Craig on Monday 16th February 1807 in the 18th year of his age”.

Another clue, a short walk from Livingston Inn, is the B listed Scottish Historic Building called The Old Toll-house (a private residence), West Lothian’s last remaining toll-house still standing by the side of the original turnpike road now called Old Cousland Road.

The arrival of the railways in the mid-1800’s and rail travel between Edinburgh and Glasgow saw a steep decline in the stagecoaches’ fortunes as all eyes turned to the train.

Information from West Lothian Councils Museum Service and

The Bathgate Book edited by William F. Hendrie and Allister Mackie

……………………………………………….

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, July 2012

Filed under: West Lothian | Tags: Livingston, Livingston’s 50th, volunteers, West Lothian

2012 promises to be a glittering year, crammed full of memorable occasions. The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Day falls in June, and hopefully we’re in store for a gold, silver and bronze-filled summer at the London Olympics. But closer to home and first out of the starting blocks, are Livingston’s own celebrations. The town’s golden anniversary takes place on the 17th of April, 50 years to the day since it was officially designated a new town.

2012 promises to be a glittering year, crammed full of memorable occasions. The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Day falls in June, and hopefully we’re in store for a gold, silver and bronze-filled summer at the London Olympics. But closer to home and first out of the starting blocks, are Livingston’s own celebrations. The town’s golden anniversary takes place on the 17th of April, 50 years to the day since it was officially designated a new town.

Five decades ago, in the spring of 1962, that optimistic season of growth and renewal, Livingston Development Corporation (LDC) began the mammoth task of creating Livingston New Town, a new community, and the fourth of Scotland’s post-war towns. An explosion of energy and drive meant it quickly grew from three small, existing villages – Livingston Village, Livingston Station and Bellsquarry, to today’s thriving town (population 55,000). It’s now the seventh largest town or city in Scotland.

Construction work began on the hillside above the River Almond and the omens were good – the Beatles were starting out and the Apollo Space Programme was about to take off. The hill teemed and crawled with trundling lorries, cement mixers and diggers criss-crossed the land, like a strange sort of mechanical courtship dance – and the happy result was the first major housing development in the new town, Craigshill. The LDC’s plan expanded the town from east to west and the neighbourhoods of Howden, Ladywell, Knightsridge, Dedridge, Eliburn, Deans, Carmondean, Bankton and Murieston quickly followed.

As the community gears up to celebrate, Livingston’s MP, Graeme Morrice, in a late evening Adjournment Debate in the House of Commons recently, highlighted this significant milestone in Livingston’s history. To the sound of Big Ben striking 10 o’clock, he spoke of Livingston’s great successes and achievements, and paid tribute to some of the many individuals and groups that have contributed to Livingston’s remarkable success story. He felt Livingston’s most valuable asset was “its people,” and a key characteristic of the new town’s population is the diversity of the backgrounds and experience that people have brought to Livingston. Its 50th celebrations “will rightly involve the local community, its schools and voluntary groups.”

Livingston has a dedicated army of unsung heroes in voluntary and charitable groups who reach out and connect – get involved and give something back to their community. They help make it tick.

Livingston has a dedicated army of unsung heroes in voluntary and charitable groups who reach out and connect – get involved and give something back to their community. They help make it tick.

A voluntary community group in Dedridge, formed in 2007, the Dedridge Environment Ecology Project (DEEP), has been working tirelessly on improving their local environment. Wilma Shearer and Roley Walton are two of the group’s volunteers. Wilma, 75, is DEEP’s Secretary and Roley, 82 (and proud of it!), is Vice-Chairperson. Between them they have lived in the area for about 70 years. Looking back to a time before DEEP began their work, Wilma remembers birds nesting amongst dumped trolleys and piles of rubbish in the area. She felt this was a shame because, “I love nature, the birds, trees, flowers.” Wilma, Roley and other local people made a habit of picking up litter (and still do) and the council helped with uplifting bigger items but it wasn’t till DEEP came about that a real difference was made. “I love seeing the results of what we’ve done,” says Wilma.

Roley, a retired Biology teacher, joined the group at the outset. “We’ve been able to make changes in an area that really needs it,” she says, “I love, LOVE, seeing habitats restored.” The teamwork is something else she enjoys. The wider community gets involved, school children and teachers from 5 local schools muck in and enjoy the fruits of their labours, like Nature Trails and pond dipping. The scouts and the minister have lent a hand too. “We get great help,” says Wilma. The group has transformed the area known as Dedridge Plantation with pond restoration, woodland management and paths widened which means more people can use the wood – mums with buggies and wheelchair users.

The volunteers of DEEP now have their sights set on the Dedridge Burn corridor. This project started in October 2011. The aim is to form a wildlife network along the line of the Dedridge Burn into the heart of Livingston and linking with the River Almond. For this to happen the volunteers – sleeves rolled up and trusty wellies on – plan to make a connected series of attractive and biologically diverse areas along the burn, a place for local people, visitors and wildlife to enjoy. Already, they are planning the grand opening in April of the restored Wave Pond, renamed the Jubilee Pond, in honour of Livingston’s 50th and the Queen’s 60th anniversaries. A lucky local school pupil (name will be drawn from a hat), will cut the ribbon.

The volunteers of DEEP now have their sights set on the Dedridge Burn corridor. This project started in October 2011. The aim is to form a wildlife network along the line of the Dedridge Burn into the heart of Livingston and linking with the River Almond. For this to happen the volunteers – sleeves rolled up and trusty wellies on – plan to make a connected series of attractive and biologically diverse areas along the burn, a place for local people, visitors and wildlife to enjoy. Already, they are planning the grand opening in April of the restored Wave Pond, renamed the Jubilee Pond, in honour of Livingston’s 50th and the Queen’s 60th anniversaries. A lucky local school pupil (name will be drawn from a hat), will cut the ribbon.

Graham Gilmour, a Test Analyst for Sky, is a volunteer too, this time with Radio Grapevine, West Lothian’s Hospital Broadcasting Service. Radio Grapevine has charitable status and broadcasts to 550 bed St. John’s Hospital in the town. The award-winning station is manned entirely by volunteers (40 of them) and broadcasts 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to the patients and staff of St. John’s. Graham, from Blackridge, presents a show on Thursdays between 5pm – 7pm and is also the radio station’s treasurer. He has been volunteering at the station for 12 years, and says, “I enjoy it so much.” Hospital radio is different, Graham feels, because collecting requests on the wards gives you contact with your audience. “I like the personal contact, chatting to the patients about music. It’s very rewarding. And a bit self-indulgent at times!”

The radio station, granted charitable status in 1991, relies on the support of the generous companies of West Lothian to make it work. The extensive library of over 45, 000 songs carries almost every kind of music that you can name – with the occasional obscure request from time to time! The studio in St. John’s is equipped with CD Players, MiniDisc Players, a turntable and an automated computer play-out system . Look out for Radio Grapevine at Gala Days and Fun Days in the community.

Many community events, activities and exhibitions are planned on and around Livingston’s anniversary. Happy 50th birthday Livingston. As Burns said, “Here’s tae us. Wha’s like us?”

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, April 2012

Filed under: West Lothian | Tags: Laird o’ Livingston, Livingston, Livingston Peel, Patrick Murray, physic gardens, West Lothian

Eliburn South’s Peel Park was once the location of the Laird O’ Livingston’s physic garden. Patrick Murray (1634 – 1671), had a passion for collecting and growing plants. Described as “one of the most promising men of science of his time”, Murray’s physic garden in the grounds of his home at Livingston Peel stocked 1,000 species of plants, and when he died, this invaluable collection became the foundation for today’s Edinburgh Botanic Gardens.

Physic gardens were European medieval medicinal gardens where medicine, botany and gardening inter-linked and doctors were as well known and influential in botany as medicine. Botanic gardens followed physic gardens when whole continents began to be discovered and shiploads of new species were brought back to Europe for scientific interest.

A botanical pioneer and “famous for collecting seeds, plants and exotica”, Patrick Murray was a good friend of Robert Sibbald (1641 – 1722) and Andrew Balfour (1630 – 1694), two Scottish physicians and botanists who went on to found the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh. The garden at Livingston inspired them to start a medical garden in Edinburgh – a place where supplies of fresh plants and herbs for medical prescriptions were on hand and medical students would study botany. Sibbald and Balfour wrote an official list for the medical profession of acceptable drugs and how to make them (The Pharmacopoeia published 29 years later in 1699), a great advance in regulating medical care in the 17th century. Work on the first physic garden for physicians in Edinburgh began in 1670.

The following year, Patrick Murray, Laird O’ Livingston, died of a fever at the age of 35 in Avignon, France whilst on a 2 year-long trip to France and Italy. Murray had bequeathed his precious plants to Andrew Balfour and the massive task of digging up and transplanting the collection got underway. Plants were carefully and painstakingly moved, cartload by cartload, to a rented 40ft x 40ft allotment in St Anne’s Yards, in the grounds of the Palace of Holyrood House, the site of today’s public car park for the Palace and the Scottish Parliament. Five years later with the garden flourishing, the plants were uprooted again, to a bigger plot of land leased from the Town Council – next to where platform 11 in Waverley Station stands today (a commemorative plaque marks the spot). A final move in the early 1820s to Inverleith Row, a change of name to Edinburgh Botanic Gardens and the journey of Murray’s plants was complete.

The Murray family seat at Livingston Peel was a fortified stone tower on a large, earthen mound and surrounded by a moat built in 1124 by de Leving, a Flemish nobleman invited to Scotland by King David 1. In return for military service to the king, de Leving was given a grant of land. Other more humble dwellings sprang up around the tower with the people attracted by work and its protection. The settlement became known as Leving’s toun, then as time passed, this name became Livingston. A street sign near the entrance to Peel Park holds on to the old spelling – Leving Place – a connection with the past.

Originally from Elibank in Peebles-shire, the Murray family acquired Livingston Peel and surrounding lands in 1512. Livingston was a huge but sparsely populated parish (around 2,000 inhabitants), stretching 10 miles from Dechmont in the east to Fauldhouse in the west. Mainly, it was rough, open countryside, dotted with small patches of cultivated land and large areas of wet moorland like Drumshoreland, Easter Inch, Whitburn and Fauldhouse moors.

In 1995, Livingston Development Corporation (LDC) commemorated Patrick Murray’s contribution to the natural science of botany by recreating a physic garden in Peel Park, the site of Murray’s original garden. At the heart of the LDC’s garden, an information panel and diagram (sadly now hard to read) shows the layout of different beds – medicinal plants of 1670, culinary herbs of 1670, medicinal plants used from 1670 to the present day – although now, ivy swamps the other plants. Box and yew hedging give structure, dividing the beds and bordering paths and other larger, open spaces, tempting you to explore. Rows of lollipop-like trees line ramrod-straight walkways leading off in all directions like the points of a compass and give the garden an open, spacious feeling. The only survivors from the old estate are the mature trees.

About 30 paces from the information point, the LDC built a circular grass mound surrounded by a cobblestone moat, a wooden bridge and 16 steps take you to the top. This simple structure represents the original Livingston Peel. Although Patrick Murray lived in the Peel, his nephew who inherited the estate, built a substantial manor house close to the Peel called Livingston Place. A low stone wall erected by the LDC on the line of the original manor house’s foundations give an idea of its size. A fitting tribute to the Laird O’ Livingston saw Lord Murray of Elibank plant Livingston’s 500,000th tree on the new town’s 10th anniversary in 1972 in the recreated Patrick Murray Physic Garden.

Plant collectors risked life and limb on their quests for new species. Like Murray, they had a thirst for knowledge and were driven by a need to explore nature and share their discoveries – our landscapes were shaped by their efforts.

Information from West Lothian Local History Library and The Sibbald Physic Garden by Dr M A Eastwood

……………………………………………….

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, June 2012

Filed under: West Lothian | Tags: Almondell House, Kirk of Calder, West Calder library, West Lothian

We have a rich architectural heritage in the West Lothian area and are spoilt for choice when it comes to delving into our old buildings’ histories. I stuck a pin in a local map and came up with a vanished country house, a centuries-old church and an art nouveau library, all with fascinating stories.

Almondell House

Almondell and Calderwood Country Park was once the setting for Almondell House, the country retreat of the Honourable Henry (Harry) Erskine (1746 – 1817), a younger son of the 10th Earl of Buchan. Almondell was then a private estate belonging to the Erskine family and here, in stunning surroundings of woodland and a river valley, Erskine designed and built his mansion in 1786 – the building had major flaws in its design and construction however, and was demolished in 1969.

Almondell and Calderwood Country Park was once the setting for Almondell House, the country retreat of the Honourable Henry (Harry) Erskine (1746 – 1817), a younger son of the 10th Earl of Buchan. Almondell was then a private estate belonging to the Erskine family and here, in stunning surroundings of woodland and a river valley, Erskine designed and built his mansion in 1786 – the building had major flaws in its design and construction however, and was demolished in 1969.

Almondell House had a two-storey centre section flanked by pavilion-roofed wings and stood where today the car park for disabled visitors is situated. This is a short distance from the Visitor Centre which occupies the former coach house and stables. Next to this, part of the walled kitchen garden still stands.

Erskine was an outstanding lawyer and politician with a great social conscience and was known as the “poor man’s advocate”. His illustrious career included two spells as Lord Advocate for Scotland, Dean of the Faculty of Advocates and Member of Parliament, first for Fife, and then for Haddington and Dumfries. But an architect Erskine certainly wasn’t. “The roof would not keep the water out,” said his son, “and the foundations would not let it away.” All the same, a young relation of Erskine, Henry David Inglis Esq., always looked forward to holidays at Almondell. He wrote in the Edinburgh Literary Journal of the mail coach setting him down (always with his fishing tackle) at Almondell gate, about ¾ mile from the house, and “the beauty of that secluded domain.” And, best of all, a melon from the garden’s melon-bed.

The house and estate remained in the family until the 1950’s. A fire caused extensive damage to the building in the 1960’s which hastened its end. In 1971, the estate was officially designated as West Lothian’s first country park.

Kirk of Calder

A building that has stood the test of time is the 16th century Kirk of Calder in Mid Calder’s Main Street. It is an Historic Scotland Grade A listed building. The church has impressive Gothic, pointed arches and solid Ashlar blocks make up the walls. These are prepared stonework – dressed or cut. The blocks are usually 35cms (14ins) in height, rectangular, and sculpted to have square edges and smooth faces. Wonderful stone carvings on the outside walls catch the eye.

A building that has stood the test of time is the 16th century Kirk of Calder in Mid Calder’s Main Street. It is an Historic Scotland Grade A listed building. The church has impressive Gothic, pointed arches and solid Ashlar blocks make up the walls. These are prepared stonework – dressed or cut. The blocks are usually 35cms (14ins) in height, rectangular, and sculpted to have square edges and smooth faces. Wonderful stone carvings on the outside walls catch the eye.

Records show a church, St Cuthberts, is believed to have existed on the present site since around 1150 and this was the building Peter Sandilands became rector of in 1526. He was the younger son of the Sandilands family who had been granted the Barony of Calder and large estates in the area in 1348. The head of the family later became Lord Torphichen and acquired the lands of Torphichen Preceptory after the Reformation in 1563. This led to the church being known as St. John’s for a time. The family seat was (and still is) Calder House. Sandilands was ambitious and had St. Cuthberts demolished in 1540 to make way for a larger, and more modern replacement which he commissioned,  designed and paid for. The present church was built in two stages, the choir and vestry between 1541 and 1547 to Sandilands’ original design, and the belfry, north and south transepts added in 1863. The transepts lie across the main body of the building turning it into the “T” shape then popular in Scottish churches. The church’s bell is dated 1663 and was recast in 1876. It is still rung today and the bat colony doesn’t seem to mind!

designed and paid for. The present church was built in two stages, the choir and vestry between 1541 and 1547 to Sandilands’ original design, and the belfry, north and south transepts added in 1863. The transepts lie across the main body of the building turning it into the “T” shape then popular in Scottish churches. The church’s bell is dated 1663 and was recast in 1876. It is still rung today and the bat colony doesn’t seem to mind!

The church has an intriguing and fascinating history, as colourful as its beautiful, stained glass windows. Holes from Covenanters’ musket shots in the 17th century can be seen in the walls, “witches” were tried here, John Knox came to preach and James Paraffin Young is remembered in one of the church’s stained glass windows. David Livingstone, the missionary and explorer and the composer Frederick Chopin have all crossed the church’s well-worn threshold.

West Calder Library

West Calder library stands between Main Street and Harburn Road. The Illustrated Architectural Guide to West Lothian calls it “a jewel of a Carnegie Library”. The Public Libraries Act 1853 gave burgh councils the chance to have free public libraries by giving them the powers to raise their local tax rates by 1d in the £ to finance the libraries. The county’s population was small and raising local taxes alone would not be enough. But thanks to Andrew Carnegie, the Scot who made his fortune in the steel industry in America, the sum of £2,500 was given to the parish council for the construction of a new building (Carnegie helped fund almost 3,000 libraries in several countries).

West Calder library stands between Main Street and Harburn Road. The Illustrated Architectural Guide to West Lothian calls it “a jewel of a Carnegie Library”. The Public Libraries Act 1853 gave burgh councils the chance to have free public libraries by giving them the powers to raise their local tax rates by 1d in the £ to finance the libraries. The county’s population was small and raising local taxes alone would not be enough. But thanks to Andrew Carnegie, the Scot who made his fortune in the steel industry in America, the sum of £2,500 was given to the parish council for the construction of a new building (Carnegie helped fund almost 3,000 libraries in several countries).

At a public meeting in the Peoples Hall, the parish council’s proposals for a new, public library were passed by 178 votes to 146. A site was decided on and in 1903 six architects submitted designs. The design chosen was by a young Glasgow-based architect, William Baillie. A grand ceremony to lay the memorial stone took place on 30 July 1903 with Mr John Fyfe, managing director of Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company asked to do the honours. A bottle filled with coins of the realm was placed in the cavity of the memorial stone. A framed photograph of the momentous occasion hangs in the library today.

Baillie’s building is full of character and period details with the building work carried out by local firms and tradesmen. On the outside, red sandstone walls are carved and decorated – the words, ‘poetry’, ‘science’ and ‘history’ carved above the windows. The entrance has an art nouveau-style, curved detailing. Inside, original cream, green and yellow decorative tiles still line the stair banister, and there are etched glass panels in the large, wood- panelled vestibule. A wrought-iron, spiral staircase links the library to the librarian’s house below. The first Carnegie library in the old Midlothian County was opened at West Calder on 24th November 1903 by Lord Rosebery, former British Prime Minister. A gold key was used for the ceremony. Great celebrations followed with a wine and cake banquet provided in the library rooms and in the evening a ball was held in the Polytechnic Hall.

For more information:

Almondell Visitor Centre has a photographic display of Almondell House.

Kirk of Calder website www.kirkofcalder.com

A History of West Calder Library by West Lothian District Council Dept. of Libraries.

……………………………………………….

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, January 2012

It’s the first official day of autumn and we feel like stretching our legs so an invigorating walk to Binny Craig appeals. Binny Craig is a geologically important landmark in West Lothian and, although a modest 220 metres (721ft) high, the views from the top are anything but. Binny Craig has two faces, a rock face enjoyed by climbers and a gentler, grassy face appreciated by walkers. It is a great example of a crag-and-tail feature, the legacy of glacier movement during the Ice Age.

It’s the first official day of autumn and we feel like stretching our legs so an invigorating walk to Binny Craig appeals. Binny Craig is a geologically important landmark in West Lothian and, although a modest 220 metres (721ft) high, the views from the top are anything but. Binny Craig has two faces, a rock face enjoyed by climbers and a gentler, grassy face appreciated by walkers. It is a great example of a crag-and-tail feature, the legacy of glacier movement during the Ice Age.

An autumnal freshness is in the air as we set out, leaving the car at Uphall Station railway car park, and turning right to follow the road downhill to Uphall, before crossing the road near the mini roundabout by the entrance to Houston House and heading up Forkneuk Road. We turn left, follow the road round to the right, go left, then right again through houses and a farm track stretches ahead. Here there’s a signpost for Binny Craig and, right on cue, the crag is dead ahead.

With the traffic noise thankfully behind us, it feels as if we’ve stepped Narnia-like into another world of wide open spaces and rolling, fertile farmland. The silence is golden, as are the fields of wheat and barley and once our ears attune to the silence we hear the ripe grain in the field beside us crackling and popping like the breakfast cereal. To one side of the track, telephone wires sag beneath the weight of a hundred or so well-fed pigeons resting between meals. In the field opposite, the grain has already been harvested and about fifty hungry, jet-black rooks stride purposefully about, their strong beaks stabbing at the stubble as they search for titbits.

With the traffic noise thankfully behind us, it feels as if we’ve stepped Narnia-like into another world of wide open spaces and rolling, fertile farmland. The silence is golden, as are the fields of wheat and barley and once our ears attune to the silence we hear the ripe grain in the field beside us crackling and popping like the breakfast cereal. To one side of the track, telephone wires sag beneath the weight of a hundred or so well-fed pigeons resting between meals. In the field opposite, the grain has already been harvested and about fifty hungry, jet-black rooks stride purposefully about, their strong beaks stabbing at the stubble as they search for titbits.

The route towards the crag is straightforward and well-signposted. We leave the farm track and a path leads to a well-constructed bridge over a stream where a considerately placed bench is situated. Our goal is still in sight as we follow the public footpath bordering a field. Binny Craig’s trig point is now visible too.

The ground is rising now as we walk up a grassy track by the side of a building onto a tarmac road, walk uphill for a few paces till another signpost directs us, via a couple of sturdy gates, onto a path between fields, new livestock-proof fencing on either side. A bit of an effort is needed as we climb up rough stone steps (approx. 60) between mixed woodland and a gorse-filled hillside. Then two more sturdy gates to negotiate and a last effort up the grassy slope to the top of Binny Craig.

The panoramic views are wonderful and well worth our exertions. We catch our breath and sit for half an hour enjoying the features in the landscape. The Ochil hills across the River Forth’s floodplain, the magnificent 1.5 mile long Forth Rail Bridge, Edinburgh and, on a clear day like today, the distant, hazy shapes of Berwick Law and the Bass Rock. Closer to home, the Pentlands frame the Almond Valley spread below. A great place for children to see where they live in 3D!

You can return the way you came or if you prefer a longer, circular walk, return by way of Ecclesmachan. Once back on the tarmac road, turn left and follow this road to the village, turn right at the junction which will take you back to Uphall.

Distances: Straight there and back: 7km/4.5 miles Circular route: 8.5km/5.3 miles

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2012

First published in The Konect Directory, October 2011

Filed under: West Lothian | Tags: Chrysalis, Compass, David Wilson, Dyke Swarm, landmark project, Livingston roundabouts, NORgate, West Lothian

The Story Behind Livingston’s Landmark Project

Livingston’s Landmark Project, the design and creation of a large sculpture on a roundabout at each of the four main approach roads to the town is the work of David F. Wilson, an award-winning Perth-based Public Artist. The purpose of the project was to create distinctive, modern landmarks to help people find their way around, as Livingston, designated a new town in 1962, lacked traditional landmarks. The Landmark Project was commissioned in 1995 by the outgoing Livingston Development Corporation. The following year the LDC handed over the management and promotion of the town to West Lothian Council. Today, Livingston is the second largest town in the Lothians with a population of 55,000.

Wilson was selected because his imaginative use of stonework in other projects had impressed the LDC. He graduated with an MA in Public Art and Design in 1987 from Duncan of Jordanston College of Art and Design in Dundee. Whilst there, he was inspired by the new public artworks appearing in the city and saw for himself the benefits art and artists could have on the community. Since his student days he has completed more than forty public art projects the length and breadth of the UK. He uses traditional craftsmanship with a modern aesthetic and many of his works, like the Landmark Project, are completed on site. Wilson called the four completed stonework and copper sculptures Compass, NORgate, Chrysalis and Dyke Swarm.

Wilson was selected because his imaginative use of stonework in other projects had impressed the LDC. He graduated with an MA in Public Art and Design in 1987 from Duncan of Jordanston College of Art and Design in Dundee. Whilst there, he was inspired by the new public artworks appearing in the city and saw for himself the benefits art and artists could have on the community. Since his student days he has completed more than forty public art projects the length and breadth of the UK. He uses traditional craftsmanship with a modern aesthetic and many of his works, like the Landmark Project, are completed on site. Wilson called the four completed stonework and copper sculptures Compass, NORgate, Chrysalis and Dyke Swarm.

“I’ll always remember the first briefing meeting I had with the client,” Wilson says. “To be offered four such wonderful sites and a decent budget was a great buzz.”

He explains that his brief was pretty open in terms of materials and concepts but there was a desire for the works to try to reflect the old industries of the area, mining for example, but also to allude to the more modern technologies and industries that the area was now famous for. Livingston was one of the original ‘garden’ cities and he wanted to pick up on that also in the work and aimed for the pieces to appear to grow out of their locations. Dean Swift, who was a landscape architect with the LDC at that time, explains the thinking behind the planting on the four roundabouts. “The landscape was designed to be a continuation of the main road landscape theme (each road had a theme of tree species), but carefully arranged so as not to hide the sculptures and, where possible, accentuate them.”

Location, location, location

One of the key considerations of his planning and design, Wilson feels, was that being on roundabouts they would have to work on a couple of levels. He wanted each design to be of a simple enough form that it was easily ‘readable’ from a distance and at speed but also that it had enough interest in terms of how it was built to stand up to scrutiny if you were able to see it closer up. His intention was that the designs change shape as you move round them, not to be static but to be of interest at every point. Each site was different and how people approached or moved around influenced the work strongly. He felt that a good solution for one wouldn’t necessarily work at another location because each roundabout was of a different size and the main viewpoints differed from site to site. “So to a degree each individual design grew out of its own site,” Wilson says. “And I kept the pallet of materials as a constant to tie the whole scheme together.”

One of the key considerations of his planning and design, Wilson feels, was that being on roundabouts they would have to work on a couple of levels. He wanted each design to be of a simple enough form that it was easily ‘readable’ from a distance and at speed but also that it had enough interest in terms of how it was built to stand up to scrutiny if you were able to see it closer up. His intention was that the designs change shape as you move round them, not to be static but to be of interest at every point. Each site was different and how people approached or moved around influenced the work strongly. He felt that a good solution for one wouldn’t necessarily work at another location because each roundabout was of a different size and the main viewpoints differed from site to site. “So to a degree each individual design grew out of its own site,” Wilson says. “And I kept the pallet of materials as a constant to tie the whole scheme together.”

Inspiration

Wilson’s inspiration for the project stemmed from his interest in organic forms and how he finds the symbolism of growth very powerful. The Scottish biologist, socialist, philanthropist and pioneering urban planner, Patrick Geddes (1854 – 1932), is a huge influence on Wilson’s work. Geddes talked about the unstoppable life force of nature and the seasons, “Even in the deepest depths of winter, scrape back the top few inches of soil and there you will find buds and new life poised to spring forth.” Wilson always finds inspiration from this concept, “It’s a very powerful affirmation of life and its continuum after death,” he says. “That idea of renewal seemed very apt to the project and I hope that I have achieved getting that through into the artworks. Even the NORgate (or archway) at Deer Park roundabout, from certain views it condenses into a bud form. This was very deliberate as, again, I felt that changing the form as you moved around it would create a dynamic that would bring interest to the project.”

This feeling of renewal informs the other sculptures too, Wilson explains. The Compass sculpture on the Lizzie Brice roundabout with its angled, needle-sharp copper point signifies new life springing forth and the energy of the town thrusting upwards. The zig-zagging walls and curving stone dyke of the Dyke Swarm which hugs the Newpark roundabout on the west approach road reflects the natural materials of the town, for instance, the bings, and this is mixed with contemporary copper for the town’s new direction. The North Eliburn roundabout sculpture, Chrysalis, illustrates the development from one form into something else, growing and new life emerging. The copper at the top of this piece adds interest and also links the sculpture to the others in the project.

Construction

The project is remembered vividly by Wilson, “Trying to achieve the tight timescale was very demanding and all four sites had to be worked together.” He had only two weeks for concept design and a further two weeks to finalise and cost the project. Employing a team of men to help, stone masons, drystane dykers and labourers, he feels he must have covered hundreds of miles moving around all the sites keeping everything on track. Over the next month Wilson and his team got approvals and carried out more detailed design so they ended up with four months available to build on site, in Wilson’s words, “A big ask!” However, the project was completed a mere two weeks late, over the winter of 1995-96. Wilson used a limited pallet of materials for the build. This consisted of various types of natural stone – reclaimed dyking stone, whinstone, a yellow limestone, building rubble and copper. Farmers at this time were opening up their fields and there was a surplus of stone from their old dykes. He arranged the purchase of the dyking stone through a stone merchant as that was the only way he could guarantee the supply in the quantities that he required. The yellow limestone was sourced from a quarry in England and was used for aesthetics as it gave a good contrast to the whinstone. This can be seen to good effect in the NORgate and Compass artworks.

Asked if it had been a smooth-running project, Wilson says, “Considering the scale of the project and some of the technicalities that it threw up, and the short timescale allowed, I feel it went incredibly well. But I certainly had my bad days!” He is referring to the installing of the foundations for the soaring, 13 metre high archway, NORgate, on Deer Park roundabout – one of the biggest tasks of the whole project. Wilson had 6 concrete lorries ordered at half hour intervals, a specialist concrete-pumping lorry on hire, and a whole traffic management system in place so that the materials could be got onto the roundabout safely and efficiently. This had taken an enormous amount of preparation and organising and was a pretty stressful undertaking. It all started to go pear-shaped within the first half hour. The concrete would not pump and nobody could get it working. There were 3 concrete lorries parked around the roundabout with only a set time to offload or the costs start to spiral. The stress and tempers were rising with one driver marching onto site and berating them all for being ‘incompetents’. Luckily for Wilson it turned out that the concrete supplier had specified and supplied the wrong grade of material for pumping so he packed everybody up before lunchtime that day and went home early! It was all re-arranged for the following day and went without a hitch.

Asked if it had been a smooth-running project, Wilson says, “Considering the scale of the project and some of the technicalities that it threw up, and the short timescale allowed, I feel it went incredibly well. But I certainly had my bad days!” He is referring to the installing of the foundations for the soaring, 13 metre high archway, NORgate, on Deer Park roundabout – one of the biggest tasks of the whole project. Wilson had 6 concrete lorries ordered at half hour intervals, a specialist concrete-pumping lorry on hire, and a whole traffic management system in place so that the materials could be got onto the roundabout safely and efficiently. This had taken an enormous amount of preparation and organising and was a pretty stressful undertaking. It all started to go pear-shaped within the first half hour. The concrete would not pump and nobody could get it working. There were 3 concrete lorries parked around the roundabout with only a set time to offload or the costs start to spiral. The stress and tempers were rising with one driver marching onto site and berating them all for being ‘incompetents’. Luckily for Wilson it turned out that the concrete supplier had specified and supplied the wrong grade of material for pumping so he packed everybody up before lunchtime that day and went home early! It was all re-arranged for the following day and went without a hitch.

Of the four artworks, NORgate on Deer Park roundabout is closest to Wilson’s heart because of everything that was involved in making it. From the concept sketch through to how to build it, this was his vision. There were many technical challenges involved in getting it built and he is very proud of the fact that he was able to solve all of them. One structural engineer told him it couldn’t be built! “NORgate is very visible from the M8 and if the flight path is right you can see it from an aeroplane, as well as being visible in Google earth,” he says. “Locally it seems to be known as the ‘wishbone’ and most people you speak to know of it.”

Fifteen years on, Wilson can still recall the intensity of the project and feeling drained and deflated when he swept up and walked away at the end. Recently he was asked to give some talks about the project, in Howden Park Centre in Livingston and to a group in Broxburn. He enjoyed seeing how interested local people were in the detailed drawings and plans and getting such positive feedback. “But the whole project,” Wilson remembers , “was such a thrill!”

Copyright © Yvonne MacMillan 2011

First published in Lothian Life, May 2011